WHO appeals the masses to respond to urgent health needs in greater Horn of Africa

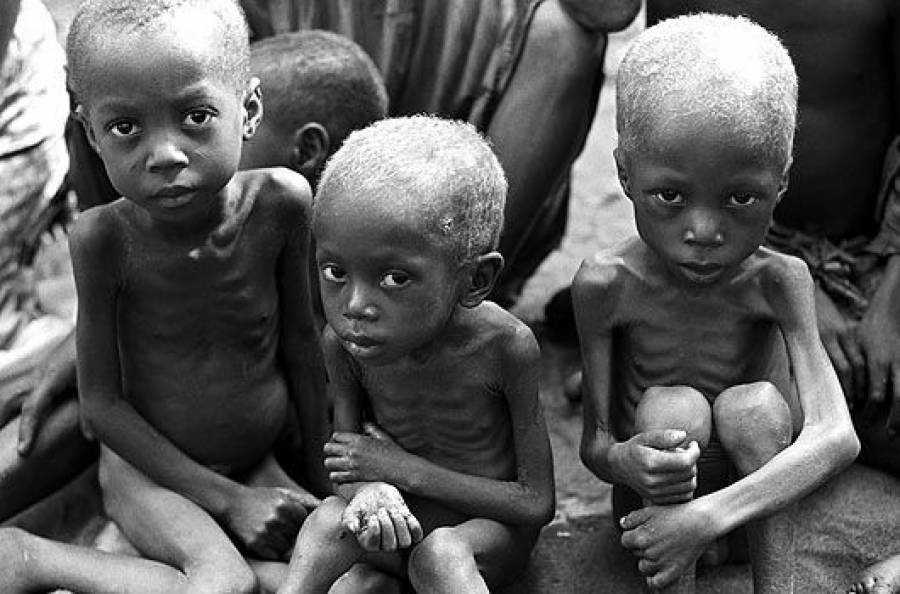

Millions of lives are in peril, including children. US$ 123.7 million is needed for the health agency’s response until December 2022.

Nairobi: The health and lives of people in the greater Horn of Africa are threatened as the region faces an unprecedented food crisis. In order to carry out urgent, life-saving work, WHO is today launching a funding appeal for US$ 123.7 million.

Over 80 million people in the 7 countries spanning the region – Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Uganda — are estimated to be food insecure, with upwards of 37.5 million people classified as being in IPC phase 3, a stage of crisis where people have to sell their possessions in order to feed themselves and their families, and where malnutrition is rife.

Driven by conflict, changes in climate and the COVID-19 pandemic, this region has become a hunger hotspot with disastrous consequences for the health and lives of its people.

“Hunger is a direct threat to the health and survival of millions of people in the greater Horn of Africa, but it also weakens the body’s defences and opens the door to disease,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “WHO is looking to the international community to support our work on the ground responding to this dual threat, providing treatment for malnourished people, and defending them against infectious diseases.”

The funds will go towards urgent measures to protect lives, including shoring up the capacity of countries to detect and respond to disease outbreaks, procuring and ensuring the supply of life-saving medicines and equipment, identifying and filling gaps in health care provisions, and providing treatment to sick and severely malnourished children.

With the upcoming rainy season expected to fail, the situation is worsening. There are already reports of avoidable deaths among children and women in childbirth. The risk of trauma and injuries is high as violence, including gender-based violence, is on the rise. There are outbreaks of measles in 6 of the 7 countries, against a background of low vaccination coverage. Countries are simultaneously fighting cholera and meningitis outbreaks as hygiene conditions have deteriorated, with clean water becoming scarce and people leaving home on foot to find food, water, and pasture for their animals.

The region already has an estimated 4.2 million refugees and asylum seekers, with this number expected to increase as more people are forced to leave their homes. When on the road, communities find it harder to access health care, a service already in short supply following years of underinvestment and conflict.

Importance of basic healthcare services and essential nutrients

“Ensuring people have enough to eat is central. Ensuring that they have safe water is central. But in situations like these, access to basic health services is also central,” said Dr Michael Ryan, Executive Director of WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme. “Services like therapeutic feeding programmes, primary health care, immunization, safe deliveries and mother and child services can be the difference between life and death for those caught up in these awful circumstances.”

WHO has already released US$ 16.5 million from its Contingency Fund for Emergencies to ensure people have access to health services, to treat sick children with severe malnutrition and to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease outbreaks.

Advertisement

Trending

Popular

Aging: New study identifies key lifestyle, environmental factors ...

-

Hair loss: Discovery uncovers key stem ...

08:00 PM, 25 Feb, 2025 -

Broccoli sprout compound may help lower ...

11:31 AM, 25 Feb, 2025 -

Gas Pain vs. Heart Attack: How to tell ...

09:00 PM, 22 Feb, 2025 -

Coconut oil supplement shows promise ...

08:00 PM, 20 Feb, 2025